JSON-P: what it is, what it's not and how it works

I thought I'd take time out from discussing the brave new world of ECMA5 (to be continued) and do a post on JSON-P, since it's occured to me lately that it's often misunderstood by intermediate developers.

This post is aimed at developers who use JSON-P but have been been too sure about what it does under the bonnet. We'll pin down what it is, isn't, how it works, and some common misconceptions.

JSON-P in two sentences

JSON-P is means of loading data from a remote server, provided the server in question is expecting the request. It is not AJAX, and does not necessarily involve JSON.

How JSON-P works

JSON-P gets around the fact that JavaScript's Same Origin Policy prevents cross-domain AJAX by exploiting the fact that the src attribute of the script tag is not subject to this limitation, and can load in content (i.e. JavaScript) from remote servers.

Therefore, the steps of a JSON-P request are as follows:

- a new script tag is DOM-scripted into the page (or an old one is re-used)

- the request URL is applied to the script tag's src attribute

- the requested server loads our request and outputs a response

- the response is evaluated as JS, since we requested via a script tag

1var req = 'http://www.someserver.com/web_service';

2var script = document.createElement('script');

3script.src = req;

4document.head.appendChild(script);

If the server's response is...

alert('hello from someserver.com!');

...the alert will fire in our page once the request completes. Likewise, if the response is...

var something = 'hello from someserver.com!';

...a global variable, something, will be set in our page.

The key to understanding JSON-P is to remember that the server's response ultimately ends being evaluated as JavaScript, since it is called by a script tag.

These are simple examples. Usually, of course, you're going to want the server to give you some data.

Accessing the server response: assignment and callback

Normally we want our JSON-P request to result in one of two things happening:

- the data is passed to a globally-accessible callback function that we've prepared

- the data is assigned to a global variable

It must do one or the other, otherwise the response will not be accessible to our page's JavaScript. So if the server simply returned:

{name: 'Fido', type: 'Labrador', age: 3}

...that data would be unreachable - even though it's valid JavaScript. This is not a trait of JSON-P but of JavaScript itself, but it is a common stumbling block for developers new to JSON-P. Think about it; if a linked script in your page contains the above, without assigning it to a variable or passing it to a function, it is inaccessible.

Assignment

We saw variable assignment in the example further up. This is useful when, say, loading jQuery from CDN; we don't need the request to call a callback - we simply want jQuery to load. In other words, our JSON-P response should simply assign the variable jQuery (the jQuery namespace on which the library's API lives).

Callback

More common is for the response to call a callback function that we have prepared. For this, the server will need to know the name of the callback function; large, public JSON-P web services allows you to specify this in your request structure.

For example, the following is a request to Twitter's JSON-P web service to retrieve five Tweets that mention Paddington Bear:

'http://search.twitter.com/search.json?q=Paddington%20Bear&rrp=5&callback=my_callback_func'

If you run that in your browser, you'll see the web service outputs JS that passes the returned data, as JSON, to the callback I requested, my_callback_func().

Imagining the Twitter web service in simple terms, if it was built in PHP, it would look something like this: (I include this only for context; if you're a front-end-only developer, don't worry too much about this).

1//get JSON-encoded Tweets

2$tweetsJSON = get_tweets_json();

3

4//output

5if (isset($_GET['callback'])) echo $_GET['callback']."(";

6echo $tweetsJSON;

7if (isset($_GET['callback'])) echo ");";

The web service fetches and JSON-encodes the tweets, then builds an output string consisting of a call to our callback function, passing it the JSON as its only argument, i.e.

my_callback_func({ /* Twitter JSON here */ });

If we hadn't specified a callback, only the JSON would be output - useless for JSON-P requests but usable by server-side cross-domain requests (not relevant to this article).

As I touched on above, it is not always certain that you'll need to tell the web service the name of your callback function. If you control the web service, you may choose to hard-code the name of the callback on the server, so our PHP would look like:

1$data = get_some_data(); //get data and format as JSON

2echo "jsonp_callback(".$data.");";

There, the server assumes jsonp_callback - so your callback will have to be called that. This is a less common scenario, but illustrates the point that, whilst the ability to stipulate the name of your callback to the web service is a convenience, it is not a fundamental component of the JSON-P concept.

Callbacks with jQuery

We've established that our callback needs to be globally accessible. Given that, you might wonder how this, a typical JSON-P request with jQuery, works:

1$.ajax({

2 url: 'http://search.twitter.com/search.json?q=Paddington%20Bear&rrp=5&callback=?',

3 dataType: 'jsonp',

4 success: function(json) { console.log(json); }

5});

There, our callback is an anonymous function, clearly not globally accessible. What we don't see, though, is that jQuery redefines it globally, assigning it a randomly generated function name (to minimise name clashes with other global entities).

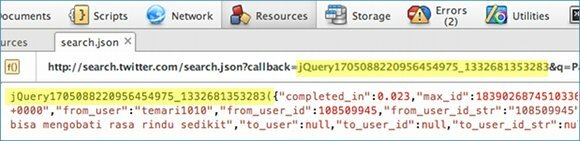

This is why we stipulated the name of our callback function as ? in the request URL rather than choosing it ourselves (though we could have done). This permits jQuery to handle this whole issue; sure enough, Opera's Dragonfly tools shows the actual request URL that was sent, and the global function that was created:

Misconceptions

Now we've taken a tour of what JSON-P is and how it works, some of the common misconceptions about should now seem obvious when you read them.

Misconception 1: JSON-P is a form of AJAX request

[UPDATE: granted, this depends on your definition of AJAX. I would hold that it's not a form of AJAX, but see the comments below for a discussion on this...]

This misconception is understandable for two reasons. Firstly, JSON-P involves the silent loading of data, just like AJAX. Secondly, jQuery implements JSON-P through its AJAX module, something that is understandable (i.e. to have a single section of the API concerned with data retrieval/submission) but can and does lead to this misconception.

As we've seen, though, JSON-P works by exploiting the src attribute of script tags, whereas AJAX requests are done over XMLHTTPRequest.

Misconception 2: JSON-P always involves JSON

The original proposal for JSON centred on the idea that servers would, on receipt of a JSON-P request, go off to the database (where applicable), get some rows of data, and serialise and output that data as JSON.

This is often the case - but it's not to say it has to be. The server response could equally be a string or a number, say.

Misconception 3: JSON-P requests must involve a callback

Again, most JSON-P web services do involve callbacks, but it does not have to be the case. As we saw early on, there's no need for callbacks when, say, loading jQuery over JSON-P - we simply want jQuery's jQuery global variable to be set.

Misconception 4: callbacks must be global functions

It's true that the callback function (or assigned variable) must be globally accessible, but this does not necessarily mean global in sense of being in the outermost scope.

1<script>

2function func() { } //global function

3var namespace = {};

4namespace.func = function() {}; //globally accessible function

5</script>

If you're using a namespace pattern like above, i.e. where your entire code exists in a single namespace to avoid global pollution, there's no reason your callback function can't be a method of that namespace. So our Twitter request from above might become:

'http://search.twitter.com/search.json?q=Paddington%20Bear&rrp=5&callback=namespace.func2'

Likewise if the web service sets a variable rather than calling a callback. You could have the server do this:

1$data = get_some_data(); //get data and format as JSON

2echo "namespace.jsonp_data = ".$data.";";

So there you have it

So there you have it. If JSON-P was hazy for you before this, I hope I've helped clear up the issue and shown you how it works under the scenes. It's certainly one of the lesser understood elements of every-day web development, but it pays to understand precisely what's going on.

For more on JSON-P, be sure to check out Kyle Simpson's JSON-P.org.

Comments (10)

Samson, at 25/03/'12 21:13, said:

Prinzhorn, at 26/03/'12 16:54, said:

Kyle Simpson, at 26/03/'12 17:00, said:

Kyle Simpson, at 26/03/'12 17:02, said:

Mitya, at 26/03/'12 17:28, said:

Kyle Simpson, at 26/03/'12 19:32, said:

Tien Do, at 27/03/'12 04:28, said:

Mitya, at 27/03/'12 11:37, said:

Sam Luden, at 6/04/'12 22:12, said:

Mitya, at 7/04/'12 12:38, said: